CHANGSHA WARES

Changsha wares were produced in kilns in Tongguan (铜官) town and Shizhu (石诸) region, about 30km north of Hunan Changsha. It is also termed Tongguan kiln (铜官窑) or Wa Zhaping kiln (瓦渣坪窑), the local name for the area in Shizhu because of the huge heaps of ceramics waste. Some of the waste is as thick as more than 4m, a testament to the enormous production scale. Archaeological surveys confirmed that the kilns were mainly located along the east bank of the Xiang river (湘江) which flows pass the Shizhu region. Changsha wares, mainly export oriented, could be ferried along this river to Dong Ting lake (洞庭湖) and from there to the Yangzi river and made its way to Yangzhou, the most important commercial centre of the Tang era.

One of the Changsha kiln sites has been developed as a tourist attraction

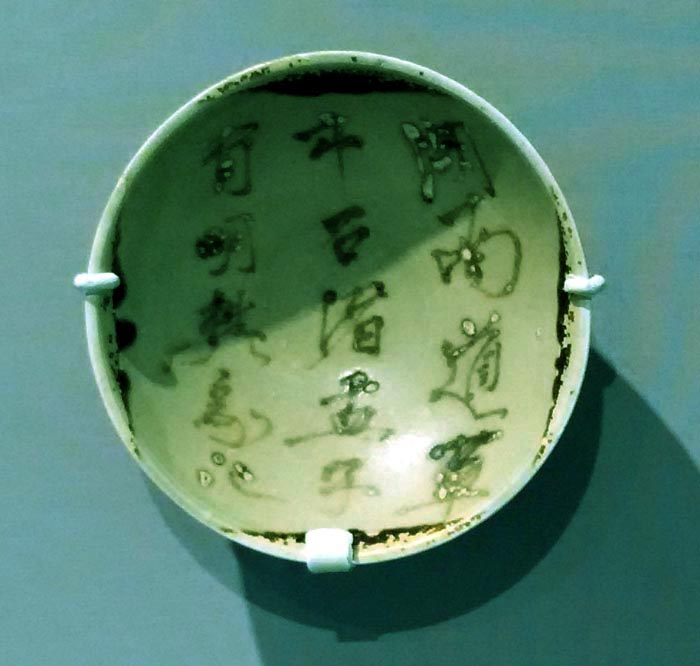

The origin of Changsha wares was unveiled only in 1950s after the kilns were discovered. Ironically, a bowl in the Tang Belitung wreck would have provided unrefutable evident of its place of manufacture. It has the following calligraphic inscription "湖南道草市石诸盂子有名礬家记". The meaning is as follows: "湖南道 Hu nan dao" refers to Hunan the region, "草市 cao shi" ie market, "石诸 Shi Zhu" ie the specific town, "盂子 Yu zi" i.e name of a vessel, "有名 you ming" ie famous and lastly "礬家记 Fan Jia Ji" ie the name of the workshop. In short, the wording specifically mentioned that it was made in Hunan in a location called Shi Zhu.

Changsha bowl providing proof of Hunan Shizhu provenance

Archaeological surveys showed that Changsha wares were first produced during 2nd half of the 8th Century and reached its peak during the Mid/late Tang period. Initial products were similar to those monochrome greenware made by Yuezhou (岳州) kiln. Hence, it is believed that Changsha ware was developed on the foundation of Yuezhou wares. This Yue character in Chinese is different from the famous Yue kiln (越) from Zhejiang. It was also a famous greenware from Hunan and mentioned in Lu Yu (陆羽)'s Cha Jing (茶经), ie Treatise on Tea.

The An Lushan Rebellion (755- 763) in Northern China inflicted devastating destruction and the ensuing social chaos resulted in mass migration of refugees to the South. Some of them were potters from Hebei/Henan who ended up in Hunan. Those potters may be instrumental in imparting new ceramics production technology to the locals. It is believed that the distinctive Changsha high-fired painted wares was developed on the foundation of low fired lead glaze sancai, a glaze formula from the north. This likely occurred towards the end of 8th century. By the time of the Belitung shipwreck dated around 826 A.D, mature distinctive polychrome painted Changsha wares were produced and quantitatively the most popular export ceramics.

Bowls with painted decoration from Belitung wreck

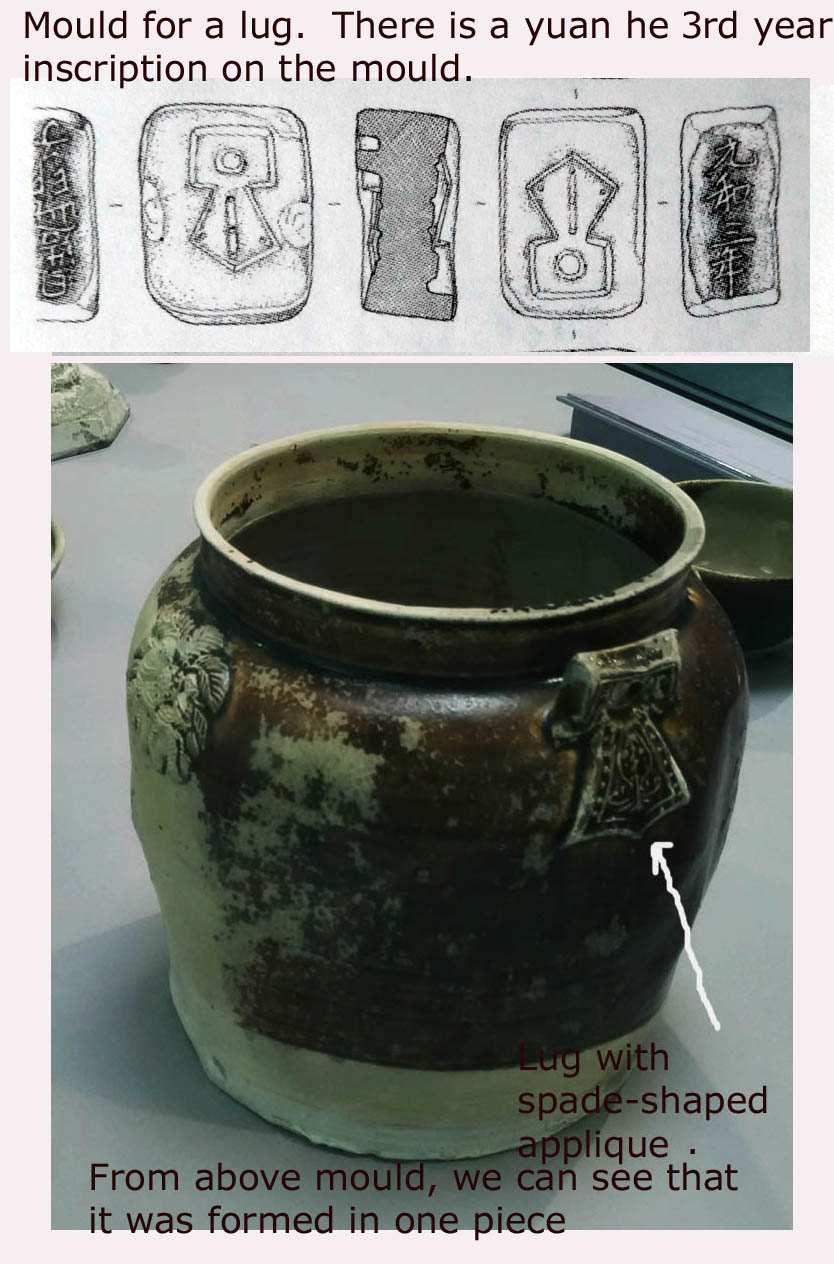

A mould of a lug, an implement for a jar, recovered from one of the Changsha kilns is useful for dating of early Changsha wares. It has an inscription Yuan He San Nian (元和三年), ie 3rd Yuan of Yuan He (808 A.D) and is currently the earliest dated example. Such lug was be popular during early 9th century. A brown glaze jar with similar lugs was recovered from the Belitung wreck.

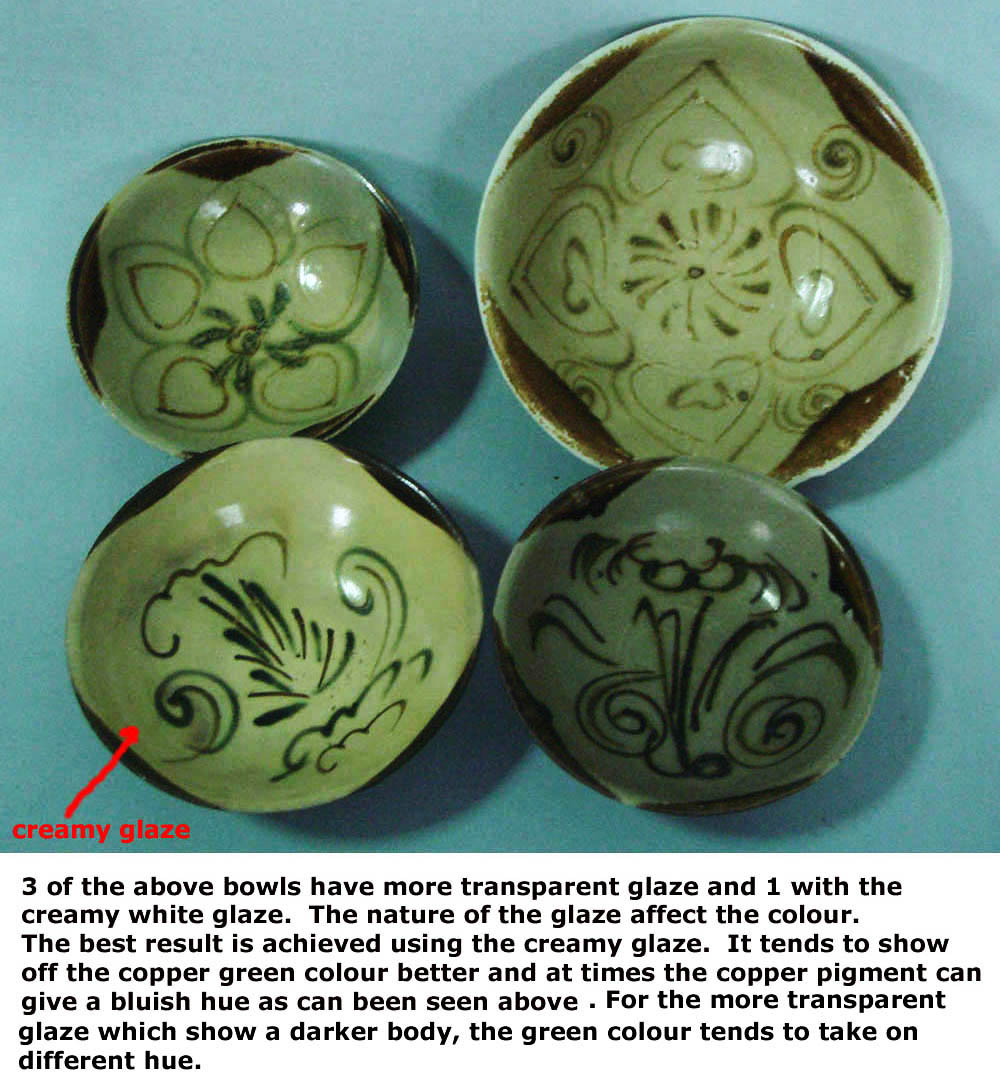

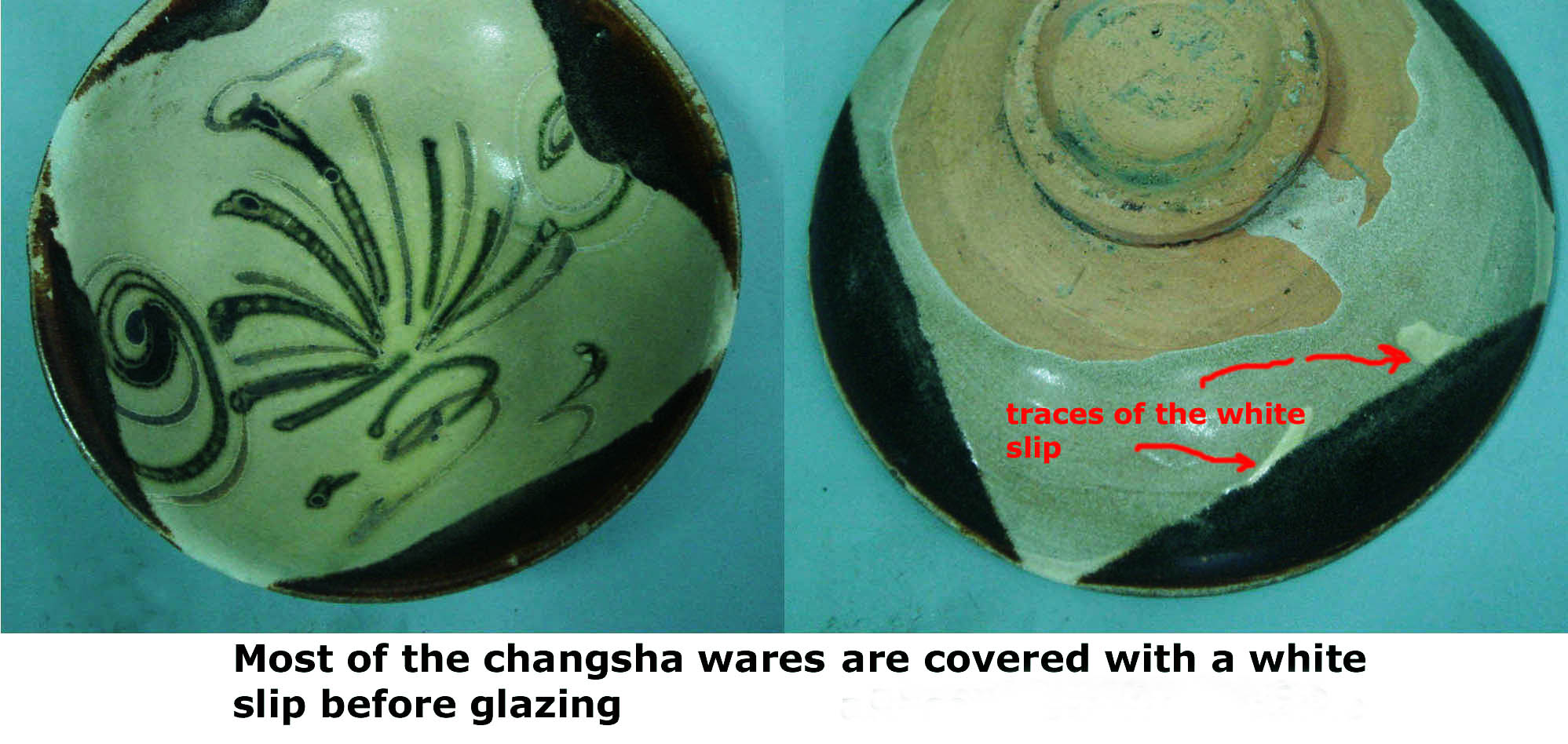

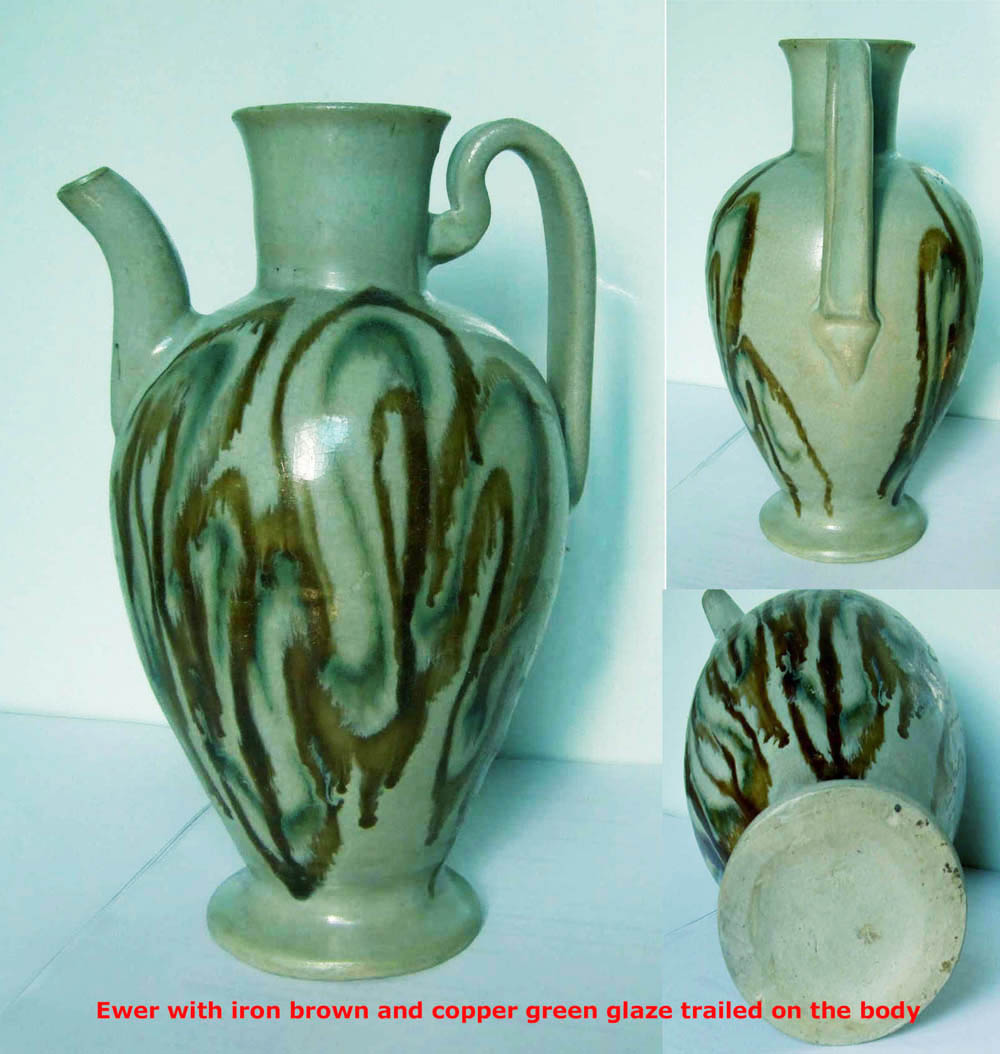

Changsha ware distinguished itself with the painted iron brown and copper green and/or applique motif on the vessel covered with transparent glaze. The colour of the glaze varies from a light grayish green to light creamy yellow. The glaze is transparent or could be translucent and milky looking. A white slip is applied to conceal the coarse body of the vessel before the glaze. The glaze has a tendency to peel off, especially from those area with brown glaze. The glaze usually has very fine crazing. The paste is usually grayish but there are examples with buff or varying brick colour tones .

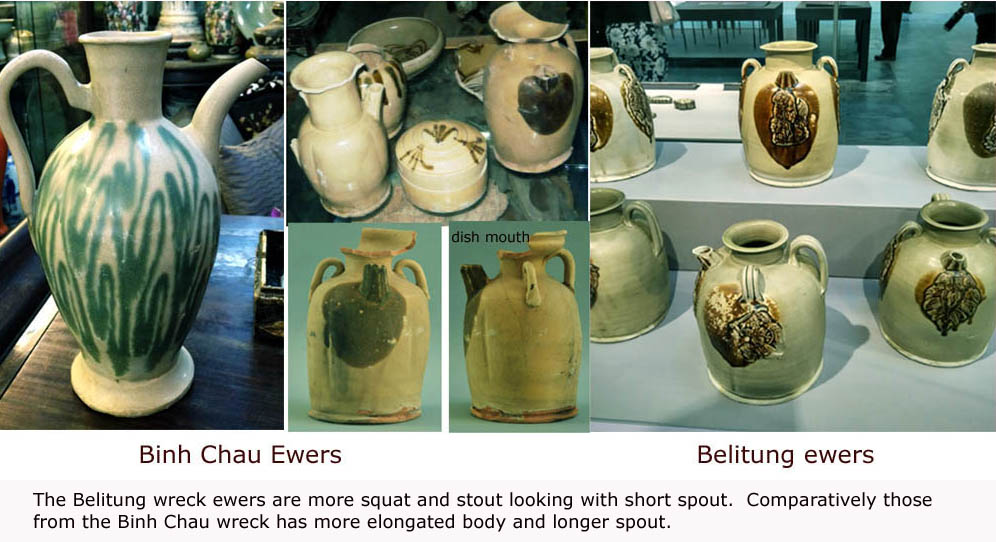

Towards the later half of Late Tang period (836 - 907 A.D), Changsha ware had evolved and could be identified by the stylistic changes in terms of form and glaze decoration. The ewer became more elongated and the spout longer. There were more varied form of bowls, many with foliated rim. The body of the bowl is no longer covered with a layer of white slip. For bowls, many have the interior bottom left unglaze and upon which is painted with decoration. A new form of abstract splashes decoration became popular. It is painted over the milky white glaze. For such decoration, the interior bottom of the bowl is glazed. Many of such Changsha vessels were recovered from the Late Tang/5 Dynasties period wreck in Binh Chau of Quangnam province in Central Vietnam.

The kilns ceased production sometime during the 5 Dynasty period (907 - 960 A.D). The Cirebon shipwreck dated to the closing years of 5 Dynasties indicated that Changsha wares were no longer exported.

Yue Celadon, Xing/Ding white ware and Changsha painted wares were the most important export trade ceramics of the Tang period. In comparison, Changsha ware was inferior in terms of potting and glaze. However, it was able to capture substantial overseas market based on its cheaper price and interesting colourful decoration. Many of the motifs have Buddhist and Islamic influences and symbolic significance. The decorations obviously satisfied aesthetics sensibility of Buddhist and Islamic consumers of Southeast Aia, West Asia and the Middle East. Many Changsha wares were found in important sites along the marine time trade route, such as Takuapa and Laem Po in Southern Thailand, ancient Borobodur and Prambanan temple sites in Central Java, Mantai in Sri Lanka and Great Mosque of Siraf. In fact, Changsha wares were discovered as far west as Malindi of Kenya in East Africa.

Dawn of Polychrome decoration

The Chinese academic circle identifies Southern celadon and Northern white wares as the main Tang ceramics production trend (南青北白). Xing white and Yue celadon wares are widely recognised as the best in the field. Strangely, Changsha wares with its innovative underglaze/overglaze polychrome painted decoration is hardly acknowledged as an important development of the Tang ceramics.

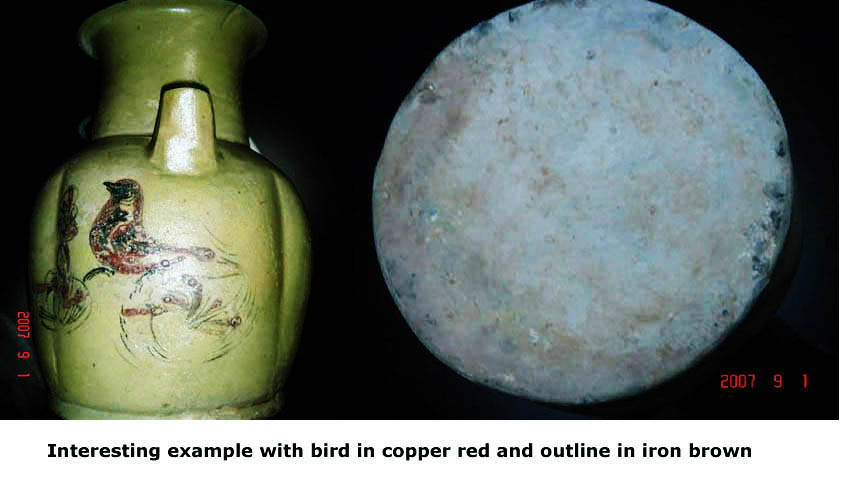

The earliest examples of painted decoration on ceramics are Zhejiang iron-brown decorated celadon vessels whch are dated to the 3 Kingdom period. But it was the Changsha potters who inherited and further explored and developed the painted decorative techniques. They were the ones who unlocked the potential of polychrome decorations. Besides continuing the use of iron brown, they introduced copper green/red for decoration. These new coloured glazes were splashed, trailed, brushed and painted on the vessels. By firing the wares under oxidising atmosphere, copper oxide glaze turns green, and iron oxide amber-brown or purple-brown with a manganese-iron pigment. There were some rare successful examples of copper red which could only be produced in reduction firing atmosphere. Indeed, the Changsha potters were the pioneers who successfully introduced high fired polychrome decorations. It was a milestone in painted decoration on ceramics and hence occupied an important position in the history of Chinese ceramics.

Red decoration from Belitung shipwreck

Polychrome motif, underglaze or overglaze ?

Currently, there is still no consensus on whether the polychrome decoration on Changsha is underglaze or overglaze. Prof. Zhou ShiRong, an expert on Hunan ceramics, is of the view that the decorations are underglaze based on physical inspection of the shards. Extensive study by Prof Zhang Fu kang of the Shanghai Institute of Ceramics showed that the designs on Changsha wares are mostly coloured glaze applied over the transparent glaze. According to him this is obvious when examining the cross section of Changsha samples. They do not show traces of the pigments on the surface of the body as oppose to those found on the under-glaze cizhou or early blue and white decoration. Typical underglaze ware has a layer of transparent glaze above the pigments but this is not apparent on Changsha painted wares. For Changsha wares, the pigment could be seen on the top and mid layer of the glaze but not on the under-layer. Some western scholars term them as in-glaze colours.

Changsha ware's Milky white glaze

Besides transparent lime glaze, Changsha wares also used a milky-white lime glaze. According to Nigel Wood, such glaze is "rich in oxides of phosphorous and low in alumina that separated in cooling into immiscible glasses. These glass-in-glass emulsions scattered white light and gave the glazes a milky cast. The white and creamy glazes of Tongguan made excellent light-coloured grounds for decoration in trailed green, brown and purple brown".

Milky white glaze became popular and the dominant form during the later part of Late Tang/5 Dynasties period. In recent years, large number of Changsha ceramics were recovered from building construction sites and the site of an ancient 5 dynasties jetty in Changsha. Large number of fragments of milky white wares with green or green/brown decorations were among the finds. The fragments have very good glossy glaze. The large number of fragments from the 5 dynasties jetty is clear evidence that Changsha wares continued to be produced in large quantity during the 5 dynasties period. Hunan was part of the Chu state (楚) established by Ma Yin (马殷). During this period, great emphasis was placed on economic development to ensure the stability of the state. The Changsha ceramics industry benefited from the ensuing peace and prosperity.

Interestingly, in 2013 some Changsha, Yue and Xing wares surfaced in the Vietnamese antique market. They came from an unknown wreck in Central Vietnam. There are also Changsha wares with milkywhite glaze and green/brown splashes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Examples of 5 Dynasties Chansha wares with trailed decorations on milk-white ground from a Vietnam wreck. The neck portion of the vase is truncated | |

Painted Decorations

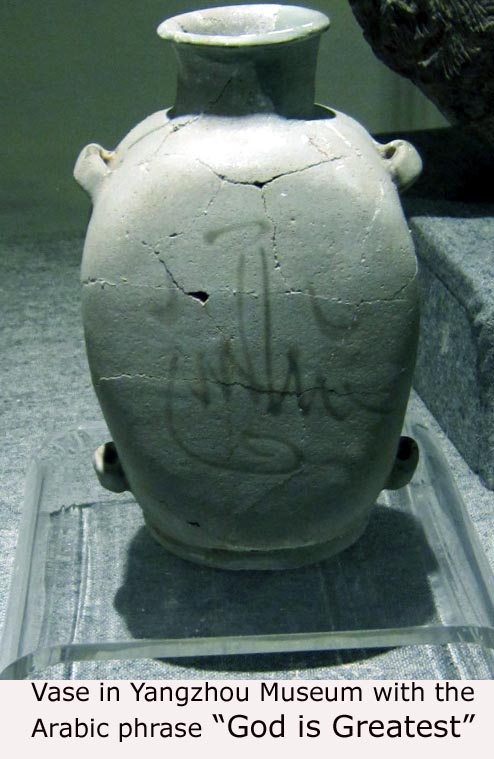

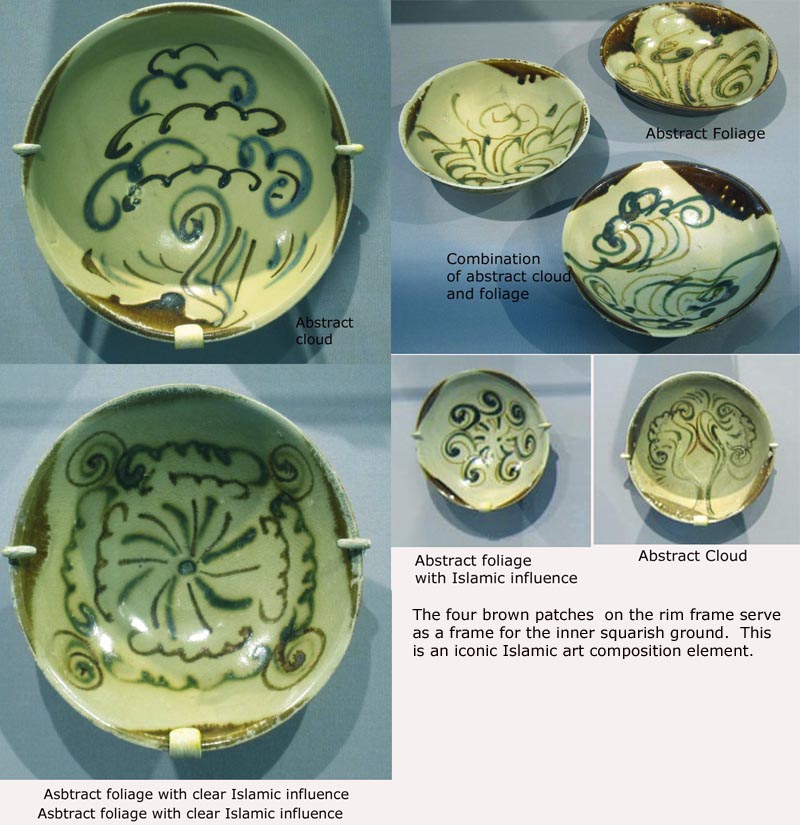

Changsha vessels bowls are decorated with a rich repertoire of motifs such as lotus, foliage/flower, abstract cloud, bird, calligraphic inscription, makara, corrupted arabic scripts, landscape, human and etc. Some of the motifs are clearly of Chinese origin such as calligraphy, landscape, Chinese human figure, bird and certain floral form. However, as Changsha ware is export oriented, majority showed Islamic or Buddhist influences. Islamic influenced motifs included those with a corrupted form of Arabic calligraphic scripts or palmette form of foliage. The use of Arabic calligraphic scripts was a common decorative technique in the Middle East. It is obvious that the Changsha potters did not know the scripts but copied them slavishly initially. Overtime, it was distorted and became a corrupted form which appeared more like abstract calligraphic lines. There is a vase excavated from a grave in Yangzhou. It was decorated with Arab script which has been identified by Islam scholars as the famous Arabic phrase "God is Greatest".

|

An example with Arabic script . It is of Arabic origin and dated to 9th cenury Abbasid dynasty. Not from the Belitung wreck. |

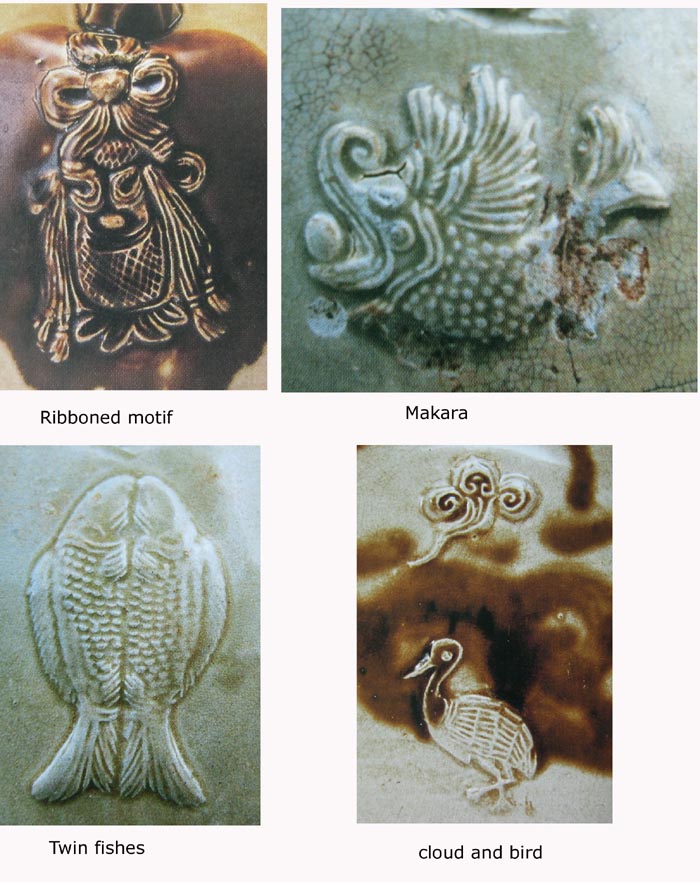

Those with clearly Buddhist symbolism included lotus and the makara.

Domestic market Lotus motif without 4 brown patches on the rim.

The decorations suggested that there was conscious effort to appeal the artistic sensibility of the Muslim and Buddhist consumer market. But from archaeological surveys, it is clear that at least a section of the consumers appeared to be cosmopolitan in outlook. They were receptive to decorations of different religious symbolism. Hence, bowls with buddhist symbolism decoration were also found in Muslim dominated Middle East and vice versa.

Besides decoration of lotus, corrupted arabic inscription and palmette foliage, the other most popular motifs are the abstract cloud and abstract foliage. In fact, majority of Changsha bowls have decoration painted on a square ground framed by 4 brown patches on the rim. This is an iconic Islamic composltion element. Islamic decoration tends to avoid using figurative images and frequently uses geometric patterns build on combinations of repeated overlapping and interlacing squares and circles. They may constitute the entire decoration or form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments.

Many of the above decorations clearly involved a different degree of abstraction with the motif modified and distorted beyond recognition. However, we do find some rare examples which depicted more realistic looking but amateurishly painted landscape.

Changsha pillow with floral motif for the domestic market

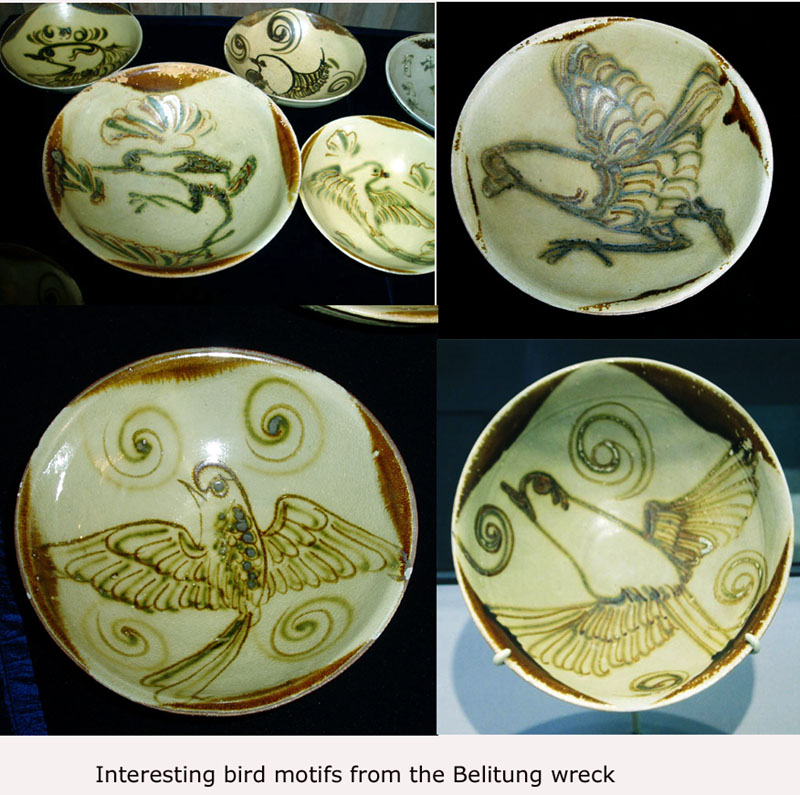

Another such category is the wide varieties of birds. Comparatively there are few and seldom found in overseas archaeological excavation. In contrast, this is a more common motif found on Changsha vessels, especially ewers, for the domestic market. There are also other painted animals such as the below galloping deer motif.

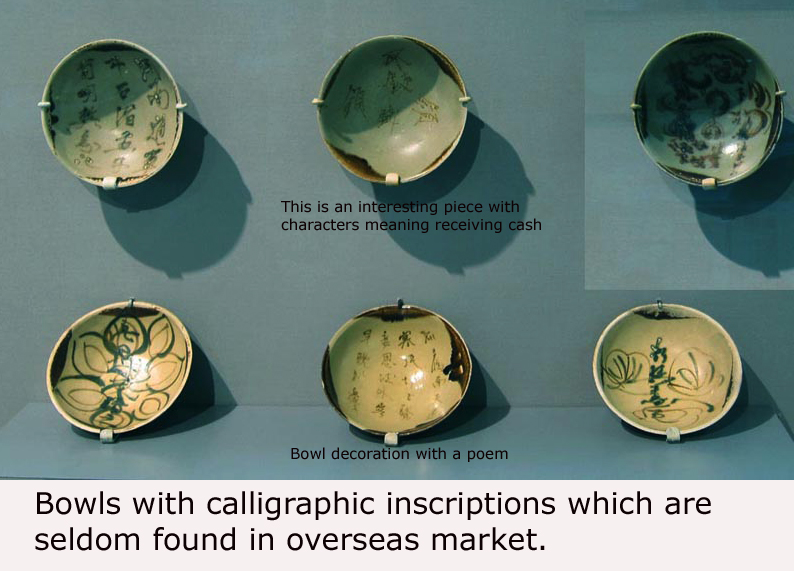

Besides the above, there are small number with calligraphic inscriptions. They are more commonly found in domestic market where its meaning is understood by the owner. The content consisted of mainly poem, maxim and idiom. However, in the belitung wreck we also find some odd inscription such as characters meaning collect money.

In the wreck, there are couple of bowls decorated with poem written in wild running calligraphic script style of Huai Shu (怀素), a famous Tang Monk noted for his accomplishment in calligraphy. They are very rare and very few examples were known to have existed.

Poetic inscription in wild running calligraphic style

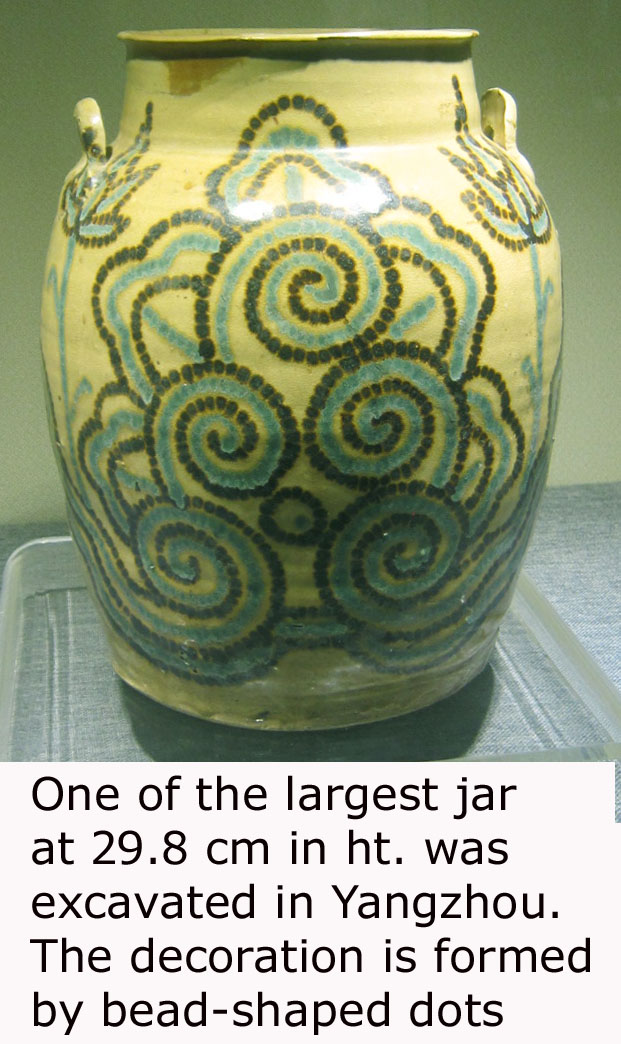

During the late Tang period, an interesting style of painted decoration with the motif outlined by bead-shaped dots was introduced.

Another interesting introduction during this period was decoration with abstract splashes which appears modernistic. Its popularity endured and continued to be produced during the 5 Dynasties period.

|

|

|

|

|

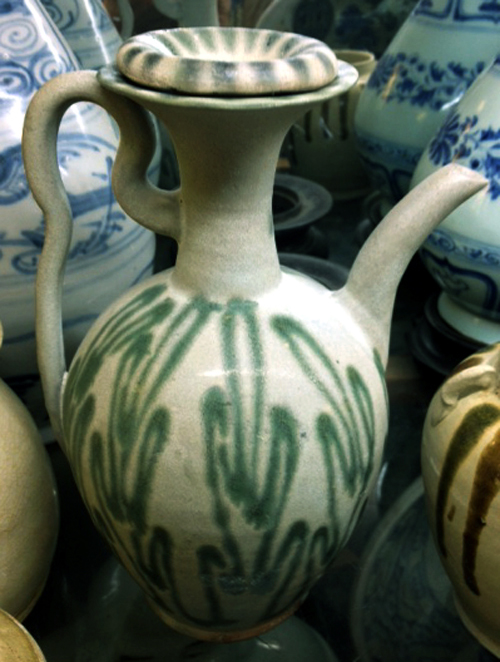

5 Dynasties ewer with trailed green motif from a Vietnam wreck. Example with cover is rare |

Incised Motifs

Incising appeared not to be a widely used decorative technique. A rare example with bird motif was found in the Belitung shipwreck.

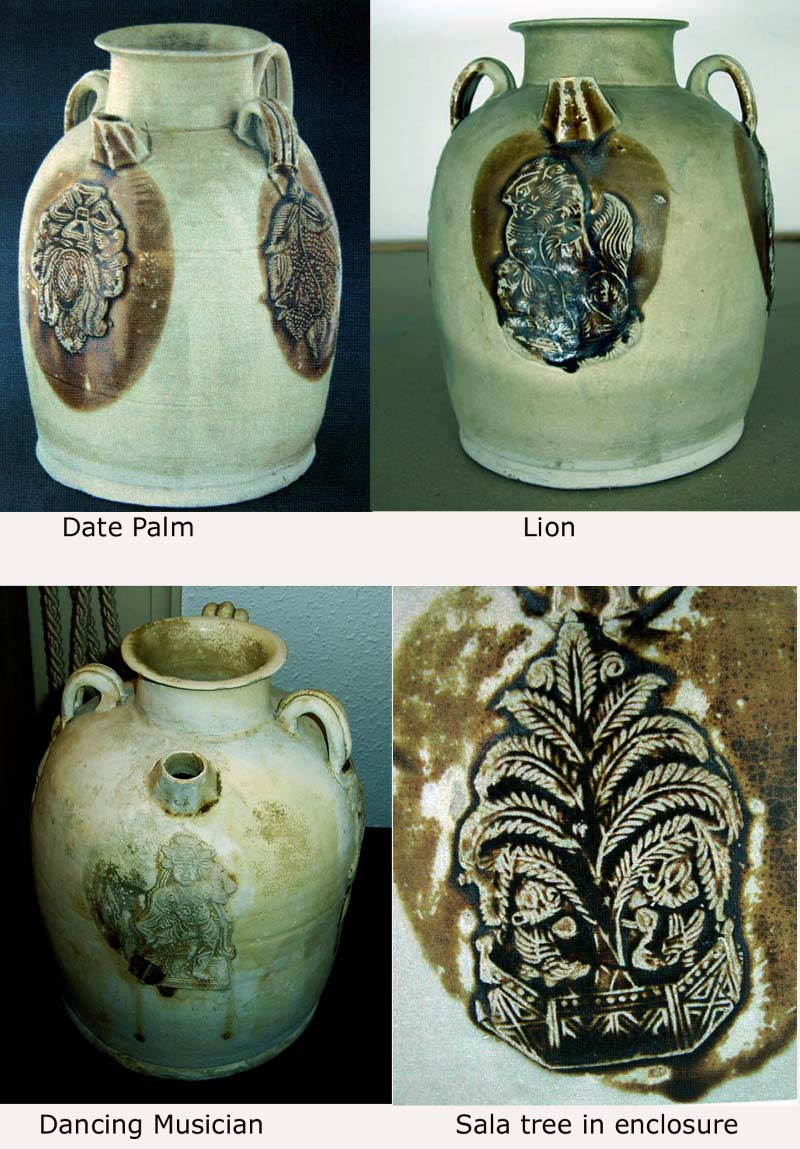

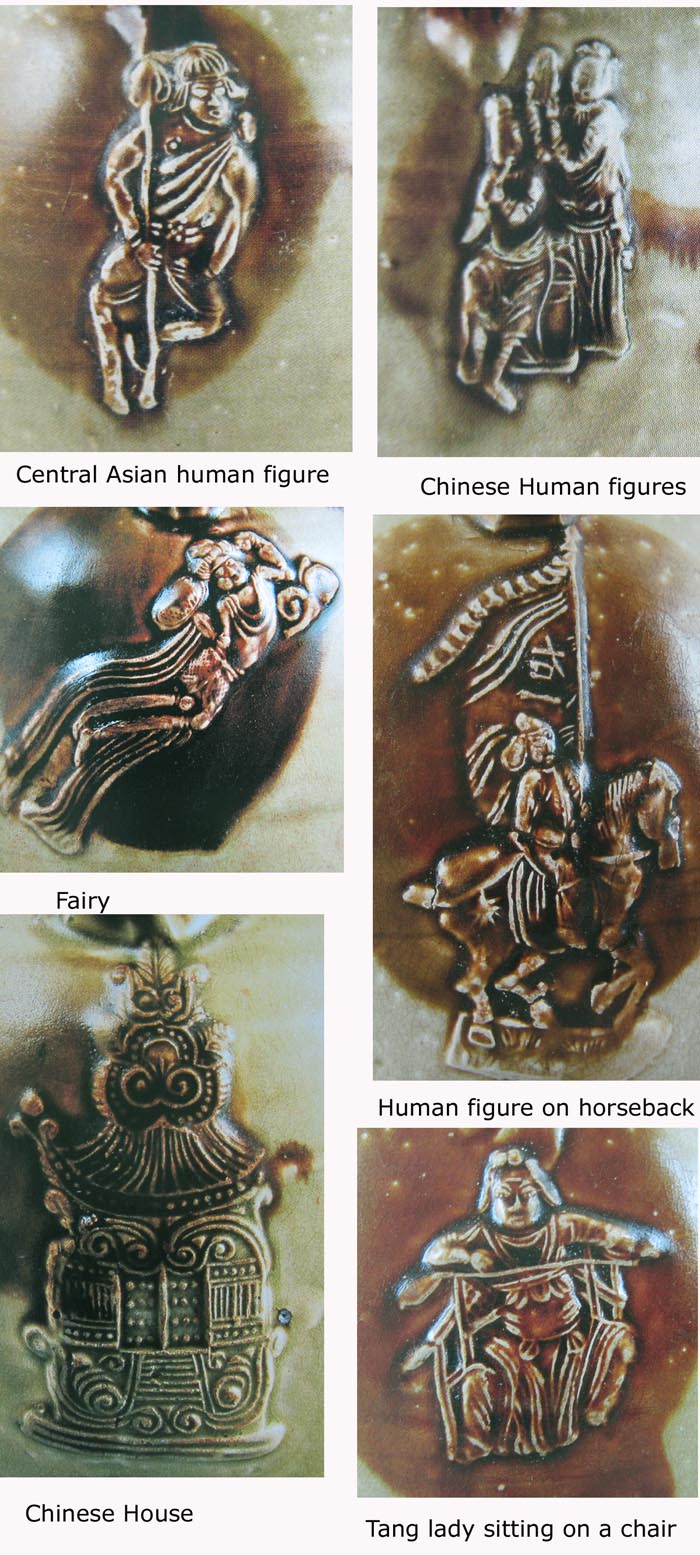

Applique Decoration

Applique embellishment, ie moulded decoration luted to the vessel was mainly found on ewers and jars. Popular motifs included date palm, lion, dancing musician, sala tree in enclosure, twin fishes, makara, Tang male and female human figures and etc. The date palm medellion is clearly a very distinctive middle Eastern decorative motif. The date palm is a flowering plant species and probably originated from lands around Iran. Those with Buddhist symbolism includes lion and sala tree applique. The sala tree is native to the Indian subcontinent and has religious significance in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Buddhist tradition holds that Queen Māyā of Sakya, while en route to her grandfather's kingdom, gave birth to Gautama Buddha while grasping the branch of a sala tree in Lumbini in south Nepal. The Buddha was also said to be lying between a pair of sala trees when he passed away. Another decorative technique is molded decorations luted onto body of wares, especially the ewers. The applique motif is covered with a layer of brown glaze. The applique molded elements include palm like tree, paired birds, lions, middle eastern human characters, pagoda and etc.

Figural Scupltures

Changsha kilns produced substantial number of small figural scupltures which included birds, animals, human and etc.

Changsha bird-shaped whistle

There were also small number of pillows with stand shaped in the form of an animal.

Changsha pillow with animal-shaped stand

Monochrome Changsha wares

Iron oxide light yellowish green and varying tone of brown glaze constituted the bulk of monochrome wares.

Monochrome yellowish green glaze lamp

Dark brown glaze bowl from the Belitung wreck

Copper was also used as the colorant for monochrome glaze. A small number of monochrome red was also successfully produced under reduction firing atmosphere. Copper oxide is a difficult pigment to work with as it is volatile under high temperature.

|

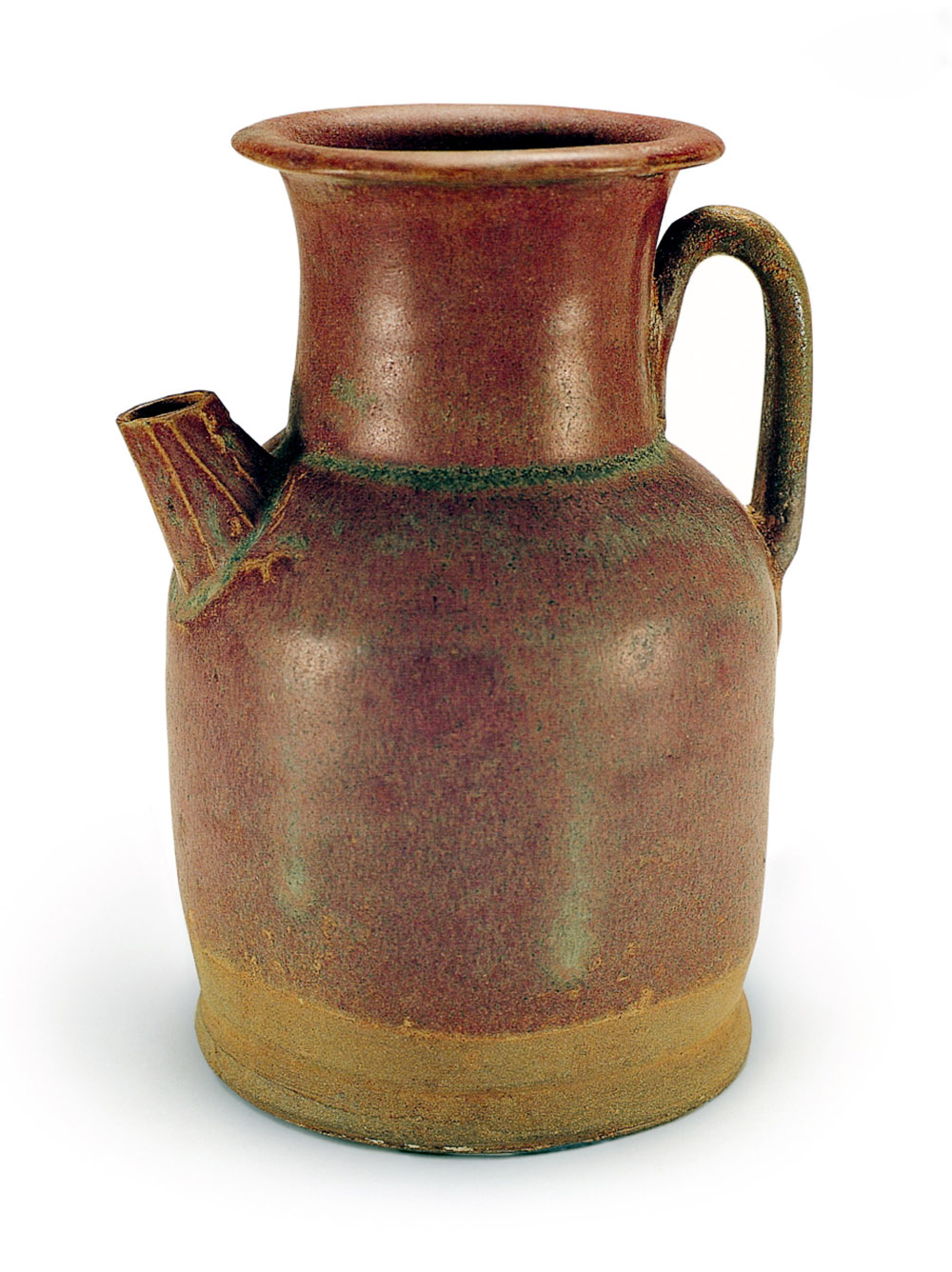

| Monochrome copper red Changsha ewer |

There were also likely monochrome copper green glazed wares produced. However, they may be confused with another group of vessels cover with celadon glaze with an opalescent bluish cast. This phenomenon is similar to that found on Jun wares of the Song/Yuan Dynasty. In view of the small number, we are not able to ascertain whether it was accidental or the potters had mastered the glaze formula to induce such effect. The glaze is still a form of celadon glaze with iron-oxide as the colorant. Under normal condition, it would resulted in green colour under reduction kiln atmostphere and more brownish under oxidation. The Jun effect can only materialised with some changes made to the glaze formula. Scientific analysis revealed that the glaze composition consisted of lower alumina ranging from around 14 to 11 %. Glaze within a range of mixture of silica, alumina, calcia and potassia induced a state termed liquid-liquid phase separation during cooling. The micro-structure showed that liquid-liquid phase separation glaze looks like caviar or frogspawn glass droplets. Through an interference effect termed Rayleigh Scattering, they scattered blue light. Hence, the bluish caste we see. It is important to understand that the colour that we see is not actual colour due to the colorant in the glaze but an optical effect.

Yuan Jun sherd with typical celadon glaze below the opalescent milky bluish cast

This Tang ewer with a strong bluish caste may also be Jun-effect glaze

Copyright by: NK Koh (11 Mar 2008), updated 27 Nov 2012, updated 20 Feb 2016)