Jun Ware

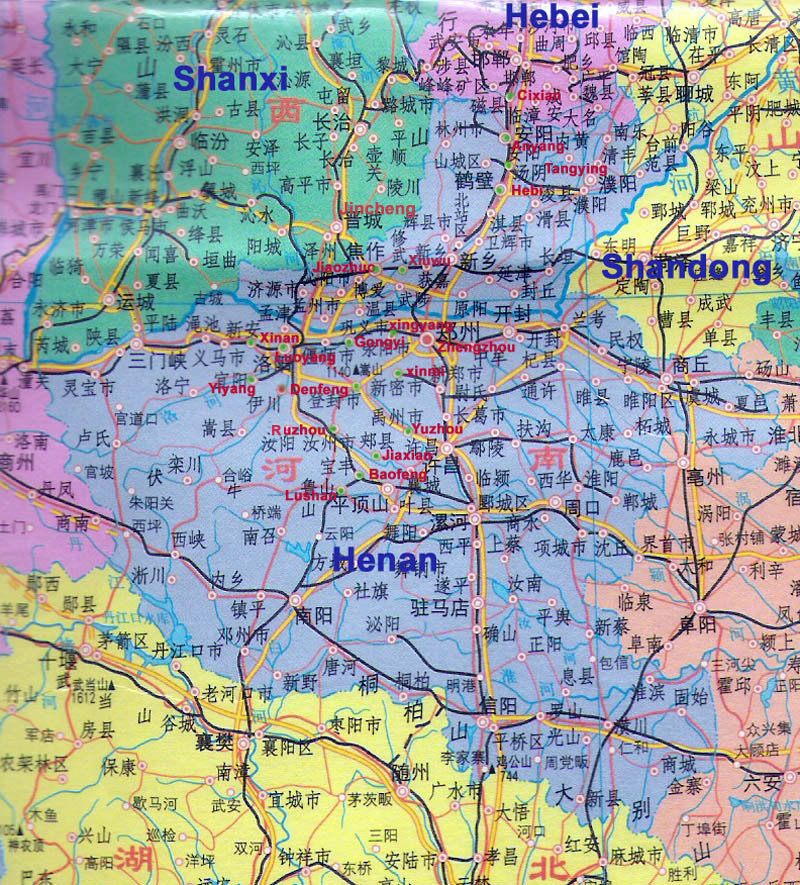

Jun ware is reputed to be one of the 5 celebrated wares of the Song dynasty. Together with Ge ware, they are the two more controversial Song wares with much still not understood regarding the wares. In the case of Ge ware, its place and period of manufacture is still subject to much debates. As for Jun ware, there are still unresolved issues such as the date it was first made and the dating of Guan Jun. The 1973-1974 excavation of Yuzhou Juntai (禹州均台) kiln has basically confirmed the actual site of production for Guan Jun. The Henan archaeologists concluded that they were produced during the Northern Song period. However, some Western Ceramics scholars are of the view that they were produced during the late Yuan/early Ming period, based on study of the form and manufacturing technique of the vessels. Some recent testings of sherds from Juntai kiln also gave a dating of Late Yuan to Early Ming period. More will be discussed later regarding Guan Jun.

Origin of Jun ware

Presently, one of the more widely accepted view is that Song/Jin Jun ware was a further development of a type of Tang black/brown ware decorated with opalescent white glaze splashes with bluish streaks. Such wares were produced in Henan Lushan Duandian (鲁山段店) , Jiaxian Huangdao (郏县黄道) and Yuzhou kilns during the Tang period. Opalescent white splashes were occasionally found on early celadon and black wares. They were the result of accidental ash-rich slag falling onto the vessels during firing in the kiln. The Tang potters may have been inspired by the observation and came out with a ash rich glaze mixture that would produce the same effect. Scientific analysis revealed that the glaze composition consisted of lower alumina ranging from around 14 to 11 %. Prof. David Kingery and Dr Pamela Vandiver, both from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, observed that glaze within a range of mixture of silica, alumina, calcia and potassia induced a state termed liquid-liquid phase separation during cooling. The micro-structure shows that liquid-liquid phase separation glaze looks like caviar or frogspawn glass droplets which scattered light. In the case of Tang Jun, the glaze is generally under-fired and hence the droplets are larger and scattered white light. When firing temperature is higher, the droplets were smaller and finer than the wavelength of blue light. Through an interference effect termed Rayleigh Scattering, they scattered blue light. Hence, the glaze will have a bluish cast. The earlier Tang Jun wares tends to be more opaque and yellowish white in colour with very little bluish streaks. Those from the later period have higher fired glaze which shows attractive opalescent white with bluish streaks. Hence, it is important to understand that the colour that we see is not actual colour due to the colorant in the glaze but an optical effect. In the case of glaze composition with alumina higher than about 15%, it will prevent the formation of liquid-liquid phase separation.

Sherds of Tang Jun

It is therefore not inconceivable that the Song/Jin Henan potters further experimented with the recipe and finally successfully produced the distinct optical blue Jun wares of the Song/Yuan period. The actual time when this occurred is still uncertain with the more commonly stated date being Northern Song to Jin period. In fact, no Jun wares from the Song/Jin period has been excavated from dated tomb. However, based on analysis of the shape of some Jun vessels, they shared close similarity with Southern Song/Jin Ding/Qingbai/Longquan/Yaozhou wares. Hence, the commencement date for Jun ware production is unlikely to be later than Jin period.

There are those who questioned the link between the splashed ware of Tang and Song/Jin Jun wares. When Prof. Qing Dashu of Beijing University excavated the Yuzhou Shen Hou Zhen Da Baiyan kiln (神垕镇大白堰窑) in 2002, he noted that layer of Tang splashed wares sherds were separated from the Song/Jin wares sherds by a layer of earth about 2 metre thick. Hence, it indicates that there is a relatively long interlude before Song/Jin wares were produced. There is therefore no clear trace of technological evolution of Tang splashed wares to Song/Jin Jun wares.

Personally I think one possible missing link that explain the rise of Jun kiln could be found in Changsha wares. There were already some Jun effect Changsha vessels found in the Belitung wreck of the early 9th century. The bluish iridiscence above the green glaze is very obvious as can be seen in below photo.

This is unlikely to be isolated accidental occurences. The Changsha potters had tested and successfully formulated the glaze receipe to induce such effect. There was continuation in the use of such glaze. One typical category was late Tang/5 Dynasties Changsha ware with brown/green splashes. Enclosed below are photos of a Yuan Jun and Changsha bowl placed together to illustrate the close semblance. I suspect this Jun effect on Changsha ware has not drawn much attention because the visual similarity on first glaze may not be apparent. The bluish cast on the Changsha example is relatively lighter in colour tone. A key reason for the difference is due to the thickness of the glaze. Jun ware has thicker glaze which actually enhances the colour.

Left Changsha bowl and right Yuan Jun dish

Changsha kilns continued production essentially until the 5 Dynasties period. The Changsha tradition was however not lost but inherited by other Hunan kilns such as those in Hengshan (衡山) during the Song Dynasty. This Jun effect glaze was widely used by the Hengshan potters. An example is shown below:

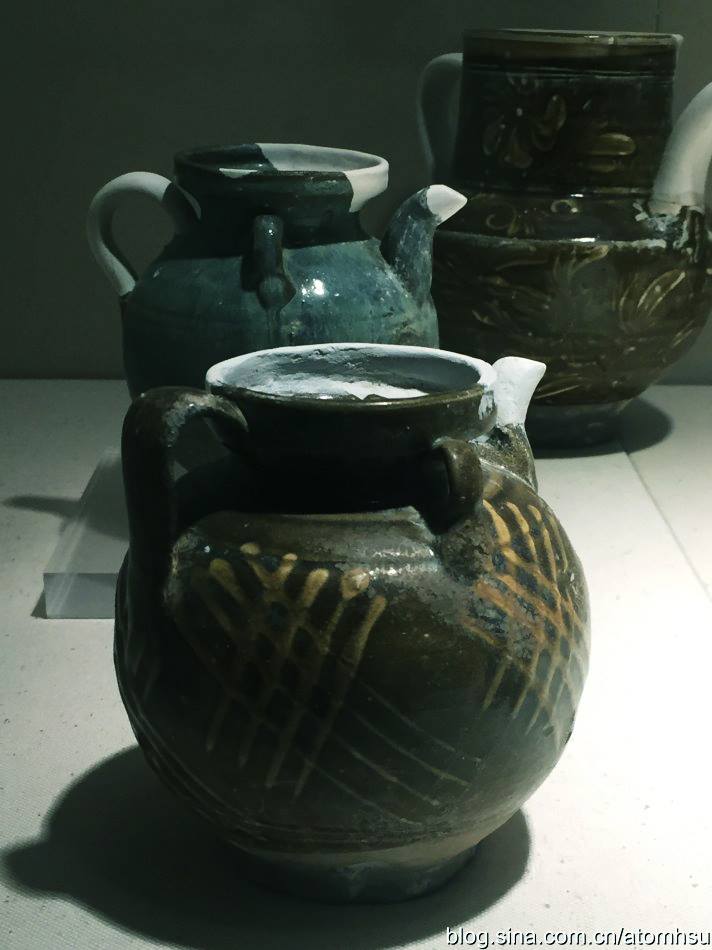

Another relatively less known region that produced Jun type glaze ware are in Hunan Xiangxiang (湘乡) city. I had a ewer from Xiangxiang kiln and had only recently identified its origin after seeing photo of one displayed in the Xiangtan (湘潭市博物馆) museum.

|

|

|

|

|

A Song Jun type glaze ewer from Xiangxiang museum |

|

| A similar example from the Xiangxiang Museum |

Other regions known to produce Jun type glaze wares were Qionglai kiln (邛崃窑) in Sichuan and Qingxi (清溪窑) kiln in Chongqing.

Example of Jun type glaze incense burner from Qingxi kiln

Hence, the production of Jun type glaze wares had an uninterrupted tradition at least since the Tang period. The production area was much wider than initially thought. If indeed there was a break in the production of such ware in Henan Yuzhou from 5 Dynasties to Northern Song, it is not inconceivable that the potters regained the technical knowledge from their counterparts in Hunan. They made further improvement to the glaze recipe. The glaze is thicker and hence enhance the intensity the colour.

Song/Jin Jun wares

From field surveys, it is observed that the Song/Jin Jun kiln sites were mainly located in Ruzhou (汝州)(previously called Linru) (the kiln at Dayu Donggou [大峪东沟] produced the finest Song/Jin Jun wares and Wu Gongshan [蜈蚣山] produced a distinctive moonwhite glaze with red/[purple splashes) , Yuzhou (禹州)(most notable site is Liu Jiamen [刘家门]), Lushan (鲁山)(notable site include Duandian) and Dengfeng (登封).

Song/Jin Jun wares are usually more thinly potted. For the bowls, the base within the foot is usually glazed and the footring wall thinner and well formed. The glaze has a fine and silky texture. The glaze could have a even bluish tone with just a hint of white or bluish tone with more cloudy white over it. The former on casual look could appear very similar to the sky blue of Ru wares. However, from the cross section of the sherds, we can see that Ru ware has a thinner glaze and the blue not as deep as those of Jun wares. In area such as the foot of Jun wares, the glaze tends to be of a olive brown tone where it thins. In the Henan ceramics circle, they termed this category as Ru Jun (汝钧). It must be noted that the glaze composition of both are different. Both have iron oxide in the glaze. The blue or green of Ru ware is the result of the colour of the iron oxide in the glaze under reduction atmosphere. Analysis of the glaze also revealed that alumina constituted more than 15% of the composition. Hence, it impeded the liquid-liquid phase separation from developing and the blue is not optical blue. In the case of the Jun glaze, analysis shows that the alumina in the composition is less than 10%. The bluish colour with or without the milky cast is the result of optical effect due to liquid-liquid phase separation.

The typical Song/Jin Jun blue with the milky cloudy cast

Some of the Jun dishes also have spur marks on the outer base. However, the spur marks are much larger than those found on Ru wares.

Some examples have spur marks on the base

Jin Dynasty entered its prosperity phase during the reign (A.D 1161 - 1189) of emperor Jin Shizong (金世宗). He was an enlightened emperor. Under his and his successor, Jin Changzhong's ( 金章宗) rule (A.D 1189 - 1208), the economy prospered and there was peace with the Southern Song regime. The Henan porcelain industry which suffered from the prolonged period of wars with the Southern Song, must have also benefited from the subsequent economic boom. Jun wares mostly likely started production earlier than mid 12th Century. During the early period of production, the vessels consisted of mainly bowls and dishes. During this prosperity phase, the quality further improved and more variety of vessels were introduced. Those Jun blue wares with red/purple splashes most likely made their appearance during this period.

|

| Jin Jun wares with purple splashes in Percival Davaid Foundation. The shape is similar to a black glaze jar dated 26th year of Da Ding (A.D 1186) in the Bath East Asian Art Museum |

|

|

Jin Jun bowls with purple splashes from a Henan grave

Jin Jun blue glaze octagonal water vessel with dragon handle. Similar examples could be found in Jin Yaozhou wares |

|

|

|

Jin Jun cover box in Percival David Foundation |

Jin Jun dish with purple splashes

|

|

|

|

Jin Jun vase |

Jin Jun Xi dish. Similar White glaze vessel was found in a Zhengnong 4th year grave (A.D 1159) |

Jin sherds of incense burner

Green Jun wares

In the Song/Jin Jun kiln sites, green Jun wares were found among the Jun sherds. They shared the same vessel forms as the typical Jun blue glaze wares. According to Nigel Wood in his book on Chinese glaze, analysis of the glaze shows that green glaze has a higher alumina percentage in the glaze. In the analysis of the Jun glaze in his book, two green Jun samples has a alumina percentage in the glaze composition of 13.2 to 15.7 respectively. The alumina percentage for blue Jun averaged around 10 or lower. The higher alumina in green Jun prevented the liquid-liquid phase separation from developing in the glaze during firing. Hence, we do not see blue and milky cast of the typical Jun wares. Essentially, they are more similar in glaze composition to the typical celadon wares. However, the glaze is thicker. Visually the glaze could be smooth and slightly opaque but could be transparent if more highly fired. Those with transparent glaze also tends to develop glaze crazings. Judging from the large number of green Jun sherds in the kiln sites, it is obvious that the potters understood the glaze composition and green Jun is a different product line. Hence, from the glaze composition point of view, strictly speaking they are not Jun wares.

|

|

||

|

Some Ru wares also have a more greenish and transparent glaze. On casual observation, they could appear quite similar to the green Jun, but the glaze is thinner |

||

|

||

Yuan Jun wares

During the Yuan period, the scale of Jun wares production expanded further. Besides those in Ruzhou and Yuzhou, kilns in many other counties in Henan, Hebei, Shanxi (山西) and inner Mongolia also produced them. The market for Jun wares appeared to be Northern China and were mainly found in graves and ancient habitation sites in that part of China. However, in Southern China, there were also some kilns in Guangxi (广西) and Zhejiang Jinhua Tiedian kiln (浙江金华铁店窑) which produced them. Some Jun wares from the Tiedian kilns were recovered from the Sinan wreck.

Yuan Jun wares are generally thickly and heavily potted. Large size vessels such as jars and vases were produced during this period. The glaze is usually scarred by pint holes and the texture of the glaze more rough as compared with those made during the Jin period. The lower portion of the outer wall of the bowls/dishes are left unglaze. This is necessary as the Yuan Jun glaze has a lower viscosity and tends to flow more freely during firing. Hence, if it is glazed up to the foot, the vessels may end up adhering to the saggar due to the overflow of the glaze.

If we examine the Yuan Jun glaze closely, we will notice that the more free flowing glaze resulted in more thinning of the glaze. It does not just occur on the rim but also on the body of the vessel. In those area with thin glaze, the colour is either olive or olive brown. In the case of Jin Jun wares, it only shows at the rim and foot area. Nigel Wood mentioned that if the glaze is too thin, they tend to absorb alumina from the clay body during the height of firing. Hence, it prevented the glaze from entering the liquid-liquid phase separation and what we see is the typical celadon colour due to the presence of iron oxide in the glaze. In actual fact, the cross section of the Yuan Jun glaze revealed a layer of olive green below the blue glaze. This layer of olive glaze is less obvious on Jin pieces but more clearly seen in Yuan pieces.

Why is this layer much thinner to the extent that we could only catch of hint of it in Jin pieces? From the Song/Jin kiln sites, there were biscuit fired pieces of Jun vessels being recovered. It indicates that the vessel was first biscuit fired before glazing. In the case of Yuan Jun, majority did not gone through the process of biscuit firing. Could it be because of this, the vessel is more porous and glaze seeps in more easily after glazing. As a result during firing, the alumina from the body mixed with the inner glaze layer more easily and impeded the formation of liquid-liquid phase separation.

As a result of the thicker olive layer and the more free flowing Yuan Jun glaze, the glaze could show a an interesting intermixing of the blue, olive and even copper red if the red splashes were added. In the case of Jin Jun, the blue cast is more even.

In some rarer example, the copper oxide gives a green and purple colour

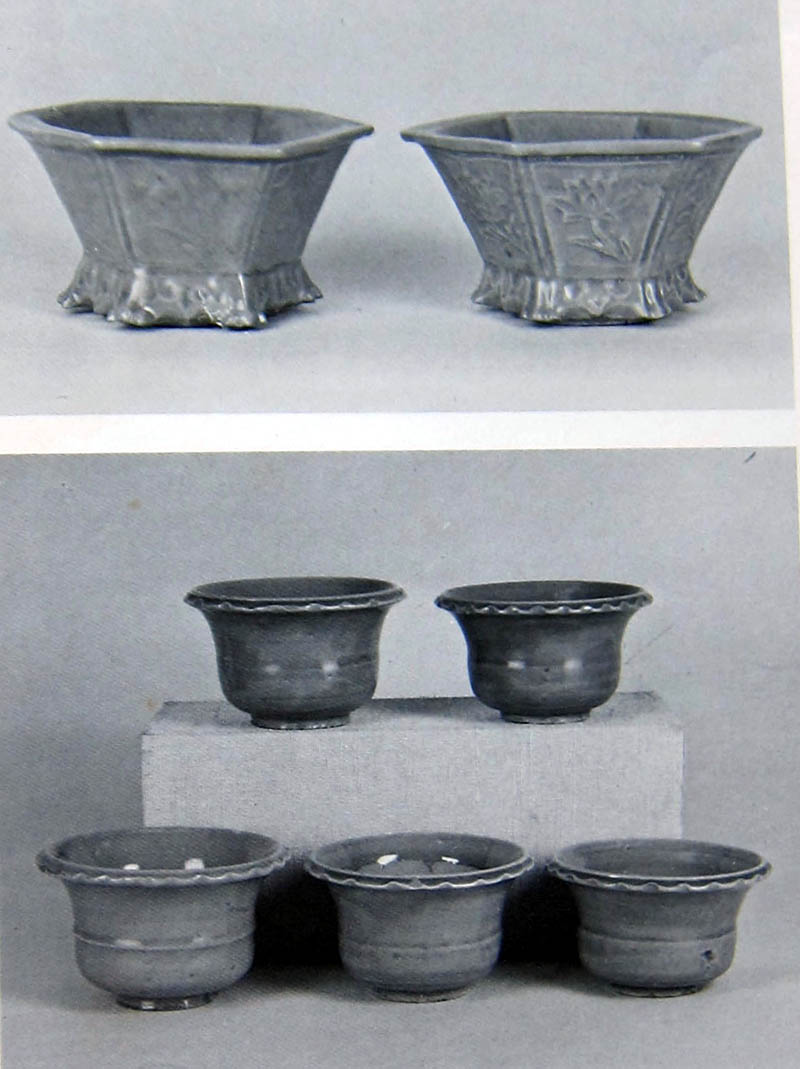

Guan Jun wares

During the 1973-1974 excavation of Yuzhou Juntai (禹州均台) kiln, sherds of flower pots, flower pot trays, narcissus bowls and archaic form of zun vases were excavated. They are similar to those extant pieces found in the Taiwan and Beijing palace museum. These are all thickly potted but well-made sophisticated moulded pieces. There are those with the sky blue glaze and others with interior sky blue and exterior a varying tone of red/purple. All these vessels have incised number ranging from 1 to 10. Research indicates that the number is related to the size of the vessel, with smaller number indicating a larger vessel. On the glaze, there are fine lines which looks like tracks left by a crawling earthworm on wet earth.

|

|

|

|

"Northern Song" Jun flower pot in the Taiwan Palace Museum |

|

\

\

Juntai kiln sherd of flower pot

Sherds of some Juntai Jun vessesl including the 3 zun vases

Narcissus bowl for flower

|

| Sherd of "Northern Song type" Narcissus bowl. The characteristic of the glaze which revealed much of the olive colour is very similar to that found on Yuan Jun |

The Henan archaeologists concluded that they were dated to Northern Song period based on the following basis:

a coin mould of a xuanhe yuan bao (宣和元宝) was recovered

sherd of a zun vase with the base incised with fenghua mark (奉华)

theory that the vessels were made for the emperor Huizong's imperial garden called Gen yue (艮岳). It was suggested the flower pots/narcissus bowls were made to plant the exotic plants and flowers

Since the archaeological excavation and findings, the Northern Song Guan Jun view was widely accepted in China. However, since the 1990s, ceramics scholars in China and Taiwan started to question the validity and veracity of the supporting evidence. In fact, in 1953 Basil Gray, a western Chinese ceramics expert, observed the similarity of the form of the Jun vessels and Ming sancai vessels. He concluded that they were dated to 15th century. In 1974, Margaret Medley suggested that based on the vessel forms, the characteristics of the glaze and manufacturing techniques, they were dated to late Yuan/early Ming. Besides, coming to the same conclusion after comparing the form of the vessels, those Chinese scholars also raised doubts regarding the coin mould and sherd with fenghua mark. For the coin mould, the veracity was questioned based on the style of the coin characters and mould. Finding such a mould in the kiln is also strange and contrary to the control and management of coin mintage. In 2003, photo of the mould was published in the book on Jun sherd "中国古陶瓷标本·河南钧台窑". The back of the mould has the character Chongning nian zhi (崇宁年制). This is a glaring anomaly. Chongning is the reign mark used by Song Huizong during the period A.D 1102 - 1106. Xuanhe Yuan bao started circulation in A.D 1119. How could the maker knew the later reign mark and made the mould in advance by at least 13 years. Although the sherd with the fenghua mark (claimed as incised during manufacturing stage) has been quoted as the proof of Northern Song attribution of Jun Guan ware, no photo of it has ever been published. Those Henan archeologists who used it as supporting evidence have also admitted not seeing it. Indeed, it is a mystery which has yet to be resolved. Even if such a sherd existed, it would further cast doubt on the Northern song attribution. Research and study of the ancient texts by Chinese scholars indicated that Fenghua referred to Fenghua Tang '奉华堂" the residence of a concubine of Southern Song emperor Gaozong. It was located in Deshou Dian "德寿殿" where Gaozong stayed after he relinquished the throne. There was no such a place in the Northern Song palace.

Regarding the theory that the vessels were made for the imperial garden, no textual evidence has yet to be found in the ancient texts. It is pure conjecture simply based on the existence of the imperial garden. If we note the aesthetic inclination of emperor Huizong, those Jun wares with red/purple glaze appeared contrary to his taste. He preferred subtle elegance in terms of the colour and shape. A good example which met this criteria would be the Ru wares which are finely and elegantly potted and has subtle sky blue colour. Scientific analysis of the sherds, purportedly from Yuzhou Juntai kiln, made by the Shengzhen Cultural Relics Archaeological and authentication unit (深圳文物考古鉴定所) and Shanghai museum indicated that they were dated to Late Yuen/early Ming period.

The Sinan wreck dated to A.D 1323 carried a type of Tiendian kiln Jun type narcissus bowl which looks very similar in shape to those produced in Juntai kiln. In the wreck, there were also some Tiendian kiln Jun type flower pots. Some of the Tiendian flower pots and a Longquan zun vase share some similarity in form, especially the stoutness, to the Juntai type.

Sinan Tiendian kiln narcissus bowl

Jinhua Tiendian kiln flower pot

Sinan wreck celadon flower pots

Sinan wreck Longquan celadon Zun vase

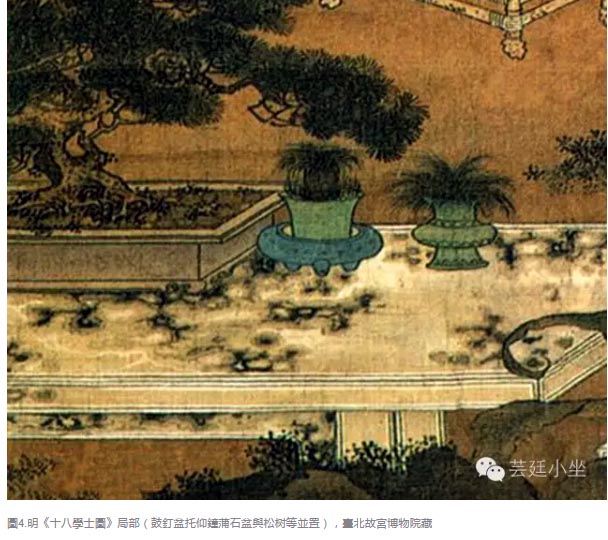

Chinese ceramics scholar Guo Xuelei (郭学雷) has written an interesting article which throws light on the actual usage of Guan Jun wares through ancient Chinese Ming paintings and quotations from Ming texts/literature. From those paintings, it is clear that Guan Jun pot and tripod basin usually functioned as a set in the planting of calamus (sweet flag). The tripod basin in fact served as a depository for water which was absorbed by the rocks in the pot. The ancient Chinese paintings also revealed that the spittoon form was also used for potted plant. The archaic Gu vase ( used for displaying flower), incense burner and the cover box to keep incense were indispensable items in the study room of scholars. The article convincingly argued that such vessels were in fact produced during Ming Dynasty for planting of Calamus, a hobby and life style activity enjoyed by the imperial family, court officials and upper class literati.

For more information, please read the below Chinese article:

http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/YzjtetdYl77iAfiQUTbUvw

In short, the accuracy of the Northern Song dating for Guan Jun is increasingly being questioned and challenged. Are those Juntai Jun vessels dated to Ming and if so, were they made specifically for the Ming Palace? These are all intriguing questions which are worth exploring further and the answer does not appear possible in the near future.

For more on the controversy related to Guan Jun wares, please read the following article if you understand Chinese:

http://ouyangxijun.blog.sohu.com/157559167.html

Written by: NK Koh (7 Feb 2012) , updated (10 Aug 2016) ,updated (26/12/2016

References:

1. Chinese glaze - Nigel Wood

2. 宋辽金记年瓷器 - 刘涛

3. 中国古陶瓷的科学- 张福康